mornings at mcdonalds

Once upon a time, I thought Mcdonald's was a fancy place. I remember the smell of sunrise dew mingled with sizzling salted pork, hot coffee in Styrofoam cups and the distinct aroma of imitation maple syrup. The spat of butter shaped like a corn cob melting onto a hotcake, and the orange juice that didn't quite taste like actual oranges, but we loved it anyway.

Now I pass a McDonald's almost every day while taking my kids to school by bicycle. Sometimes it is a a place to duck into out of the rain, our shelter from the storm.

As we sit dipping our fries into sweet and sour sauce, a man beside us pens onto a scrap piece of paper X's and O's in random patterns as if in some great effort to return a distant memory.

...

Little Ocmulgee State Park, GA

These next few blog posts will be dedicated to a class I am currently taking at Georgia State University concerning the natural environments of Georgia.

We visited Little Ocmulgee State Park on November 4, 2016 to observe the ecology of the Georgia Coastal Plain. Conditions were very dry as Georgia has been experiencing an exceptional drought. The trails through Little Ocmulgee state park are an excellent example of Sandhill and River Dune Upland Forest community, which are ultra-xeric woodland communities found within deep sandy knolls and ridges within the Coastal Plain. Little Ocmulgee state park contains Little Ocmulgee Lake which was built from the Little Ocmulgee River during the Great Depression by the Army Corp of Engineers. This harsh sand covered environment is dominated by course sand cover, with an open canopy of Longleaf pines and an sub canopy dominated by Turkey oak. Other plant species include the Bluejack oak (Quercus incana), Sand post oak, poison oak, sparkleberry, southern sand-grass, and Gopher apple. The endangered and endemic gopher tortoise is a key stone species that can be found here, and we spotted at least one burrow. We also spotted a beautiful southern hognose snake which I respectfully let slither away without a photograph.

Prescribed fire is a necessary component to keeping this community healthy and without it, hardwoods may take the place of fire adapted trees such as the Longleaf pine. While hiking here we witnessed all three growth stages of the Longleaf pine (Pinus Palustris).

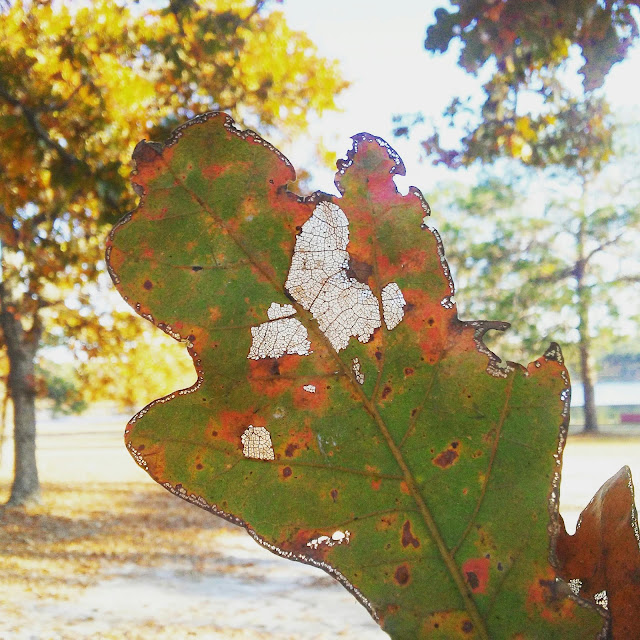

Turkey oak (Quercus laevis), Reindeer lichen (Cladonia) and Haircap moss (Polytrichum commune). Named after the fact that someone thought it's leaves are reminiscent of a turkey's foot, the Turkey Oak is one of the scrub-oak species that is often found alongside Longleaf pines.

Bald cypress, (Taxodium distichum) in all of its fall red pigmented glory.

Romantically named cypress knees, these modified roots, or pneumatophores, are created by various species in the the Taxodioideae family. Although their exact function is not known, they are believed to both help the tree exchange gases in anorexic environments (low oxygen) and stabilize the roots in muddy conditions such as the swampy areas they are commonly found in.

Arborglyph, boardwalk trail at Little Ocmulgee State Park.

The Longleaf pine (seen above) has the greatest longevity of any other pine species growing in the South, surviving 300 to 500 years. It has evolved in an environment of fire and has consequently developed a fascinating strategy to survive in such a climate, with 3 distinct stages of growth.

After germination the tree begins in the initial grass stage, where the tuffs of the needles resemble a shrub of grass. The tree then steadily stores carbon within it's roots and continues root growth underground. In the grass stage a low-intensity fire such as one mimicked during a prescribed burn does not harm the plant as it is protected by long tufts of needles. A long leaf can stay in this stage for 3 to 25 years, amazingly assuring the best possible chance of survival at all odds.

Once the seedlings emerge from grass stage they quickly bolt into what is called rocket stage, using the carbon carefully stored within the roots for a rapid growth of 4 to 5 feet in a single growing season. After this rapid growth and from about the height of at least three feet tall they are in sapling stage, where they are once again most likely to withstand the flames of a forest fire, Perhaps this is why they do it so quickly.

pictured above is a Longleaf pine seen in both grass and rocket stage

This beautiful and fragrant Eastern red cedar, (Juniperus virginiana) is an example of a species that can thrive in this type of community only if fire suppression has not been utilized. Without fire, these trees might soon out-compete those adapted to fire, such as the scrub oaks and pines.

Usnea strigosa lichen ,

growing on a branch of a small Turkey oak tree. Lichens are a true wonderment of nature, and I am still grasping how to understand them. "A lichen is a symbiosis. That means that it is two or more organisms living together such that both are more successful within the partnership than they would have been if they were living on their own.All lichens are made up of a fungal partner and either/or an algal partner or a cyanobacterium partner, or both". As of late we are also learning that lichens are very sensitive to air pollution and may be able to serve as a bioindicator of air quality.

The fast growing Slash pine (Pinus elliottii) as pictured above and below, was planted in place of Longleafs for timber once all the old-growth Longleafs were deforested in Georgia. It is native to South Georgia and Florida. On a personal note, my great- grandfather was once among the many field workers who tapped Longleaf pines for the turpentine industry and remembers when the Slash pine was being hailed as superior to the slower growing Longleaf.

Sand Post Oak (Quercus margaretta)

this lichen is unknown to me. if anyone has an idea of what it may be please comment below!

Wormsloe Historic site and the Georgia coastal marsh, Savannah, Georgia

These next few blog posts will be dedicated to a class I am currently taking at Georgia State University concerning the natural environments of Georgia.

Southern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana var) covered with Spanish Moss (Tillandsia usneoides) at Jones Marsh Creek along the public trail of Wormsloe Historic Site. Spanish moss is a native, perennial, epiphyte herb which is in fact neither a moss or lichen, It is a flowing plant, which anchors onto a host plant without taking any water or nutrients from the host. It derives water from humidity and rainfall, and nutrients from the air. Often also called an air-plant or old-man's beard, it was once commonly used by native Americans to weave bedding, rugs, and rope. I have also heard it referred to as witch's hair. Spanish moss is common throughout the Deep South.

This, to me, is what home looks like. A Magnolia grandifora, Southern Live oak (Quercus virginiana, and Spanish moss trio.

Magnolia grandiflora in bloom during the summer a little south of Wormsloe Historic Site at Jekyll Island. Magnolia's bloom throughout the summer, so none were in bloom during this November visit.

skink spotted on the maritime forest floor.

We visited the managed forest preserve, Wormsloe Historic Site and Tybee Island in Savannah, Georgia on the weekend of November 4, 2016 to experience a taste of Georgia's Maritime Ecoregion. The Maritime Ecoregion of Georgia is a small but incredibly vital one, containing the largest area of the protected maritime forest of any state on the East Coast, as well as one-third of the remaining salt marsh habitat on the entire East-Coast. This is largely due to the protection of Georgia's barrier islands thru Federal, State, and private ownership.

The distribution of Maritime forest along the coast is often interrupted by bays and inlets, or by narrower barrier islands that are not large enough to support forest growth. Although protections are under place, urban development continues to encroach upon these communities at a much higher rate than ever before as land that once was considered inhabitable or of little value is converted into golf courses and luxury resorts. It also becomes much more difficult to prescribe fire to forests who benefit from the use of fire management in places where roads intersect and housing is near by.

The Maritime Ecoregion is also characterized by Salt Marshes and Brackish Tidal Marshes, Maritime Dunes, Interdunal Wetlands, Tidal Swamps, Intertidal Beaches and Sand Bars and Mud Flats, and Freshwater Tidal Marshes.

The Wormsloe Historic Site and property is and managed by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and is open to the public as a state park. It is located on the southern end of the Isle of Hope and is bordered by Jones Creek and Jones Marsh on the East and Moon River and surrounding marsh to the West. Approximately 60% of the Isle of Marsh has been preserved in it's natural state, which includes Maritime Forest, Intertidal Marsh, and limited Freshwater Wetland habitat.

Recent trends of sea level rise are documented at 3 to 6 mm per year. (https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/sltrends/slrmap.htm)

The island core is currently 3 to 5 meters above mean sea level. Early 19th century records indicate that the hydraulic heads of artisan wells located on the property were once well above the surface, although they are now 40 feet below earth surface.

At least one well on the property showed evidence of saltwater intrusion on 11/6/2016.

On the Beach of Tybee Island we observed an example of the Maritime dune system. The texture of the beach sand is much more thick and muddy than one might expect of a natural beach, due to the course sands being dredged from the ocean floor to widen shipping lanes for cargo ships headed to the port of Savannah. You can read a little more about the $706 million project here.

We observed the ecology of the dune formation with several species of flower still in bloom. Plants of Maritime dunes may include some trees that are salt tolerate such as the Southern Red cedar and Live oak, but are mostly characterized by small shrubs and vining plants that helps to hold the sands together. We observed pennywort, Beach morning-glory, Dune hairgrass, Dune prickly-pear, Wax-myrtle, Peppervine, Saw palmetto, and Railroad vine. Other common plants of this ecosystem include Spanish dagger, Creeping frogfruit, and Groundsel tree.

These dunes are a critical nesting habitat for five of the seven known species of endangered sea turtles, with the majority of nests belonging to loggerheads and leatherbacks.

The distribution of Maritime forest along the coast is often interrupted by bays and inlets, or by narrower barrier islands that are not large enough to support forest growth. Although protections are under place, urban development continues to encroach upon these communities at a much higher rate than ever before as land that once was considered inhabitable or of little value is converted into golf courses and luxury resorts. It also becomes much more difficult to prescribe fire to forests who benefit from the use of fire management in places where roads intersect and housing is near by.

The Maritime Ecoregion is also characterized by Salt Marshes and Brackish Tidal Marshes, Maritime Dunes, Interdunal Wetlands, Tidal Swamps, Intertidal Beaches and Sand Bars and Mud Flats, and Freshwater Tidal Marshes.

The Wormsloe Historic Site and property is and managed by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and is open to the public as a state park. It is located on the southern end of the Isle of Hope and is bordered by Jones Creek and Jones Marsh on the East and Moon River and surrounding marsh to the West. Approximately 60% of the Isle of Marsh has been preserved in it's natural state, which includes Maritime Forest, Intertidal Marsh, and limited Freshwater Wetland habitat.

Recent trends of sea level rise are documented at 3 to 6 mm per year. (https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/sltrends/slrmap.htm)

The island core is currently 3 to 5 meters above mean sea level. Early 19th century records indicate that the hydraulic heads of artisan wells located on the property were once well above the surface, although they are now 40 feet below earth surface.

At least one well on the property showed evidence of saltwater intrusion on 11/6/2016.

On the Beach of Tybee Island we observed an example of the Maritime dune system. The texture of the beach sand is much more thick and muddy than one might expect of a natural beach, due to the course sands being dredged from the ocean floor to widen shipping lanes for cargo ships headed to the port of Savannah. You can read a little more about the $706 million project here.

We observed the ecology of the dune formation with several species of flower still in bloom. Plants of Maritime dunes may include some trees that are salt tolerate such as the Southern Red cedar and Live oak, but are mostly characterized by small shrubs and vining plants that helps to hold the sands together. We observed pennywort, Beach morning-glory, Dune hairgrass, Dune prickly-pear, Wax-myrtle, Peppervine, Saw palmetto, and Railroad vine. Other common plants of this ecosystem include Spanish dagger, Creeping frogfruit, and Groundsel tree.

These dunes are a critical nesting habitat for five of the seven known species of endangered sea turtles, with the majority of nests belonging to loggerheads and leatherbacks.

Southern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana var) covered with Spanish Moss (Tillandsia usneoides) at Jones Marsh Creek along the public trail of Wormsloe Historic Site. Spanish moss is a native, perennial, epiphyte herb which is in fact neither a moss or lichen, It is a flowing plant, which anchors onto a host plant without taking any water or nutrients from the host. It derives water from humidity and rainfall, and nutrients from the air. Often also called an air-plant or old-man's beard, it was once commonly used by native Americans to weave bedding, rugs, and rope. I have also heard it referred to as witch's hair. Spanish moss is common throughout the Deep South.

This, to me, is what home looks like. A Magnolia grandifora, Southern Live oak (Quercus virginiana, and Spanish moss trio.

Magnolia grandiflora in bloom during the summer a little south of Wormsloe Historic Site at Jekyll Island. Magnolia's bloom throughout the summer, so none were in bloom during this November visit.

skink spotted on the maritime forest floor.

Fiddler crab hiding in a deer print.

The southern portion of Jones Marsh, where these sands lie, has been impacted by the large-scale dredging of soils moved to construct the Diamond Causeway (1968-1972).

Saw palmetto is a groundcover found in Maritime forests and most closely associated with Longleaf pine forests. It's medicinal uses that have been known to native Americans for centuries are currently being explored, and Saw palmetto supplements can be bought in capsule form at your local grocer as a treatment for many ailments, most notably enlarged prostate in men and hormonal imbalances in women.

an unknown fungus or lichen with a pretty pastel hue

Beach morning-glory (Ipomoea imperati) found on the Maritime dune of Tybee Island.

Sunset over Jones Marsh from Wormsloe

Jones Marsh and Jones Creek at Wormsloe Historic Site

Ghost shrimp found in its hole on the forebeach of Tybee Island. (as soon as this picture was taken we sent it back home)

This lichen is my absolute favorite species. It is called Cryptothecia rubrocincta, or more commonly Christmas wreath lichen. Growing up I always heard it referred to as bubble gum lichen and that's what I still like to call it.

Hericium erinaceus,

also known as Lion's mane mushroom or bearded tooth mushroom, is often found growing on hardwoods and is both edible and medicinal and is widely consumed in Asia where is it also native. (There are some look a-likes, though, so please do not ingest any wild mushrooms unless you have done more research than just my blog post ;)

Atlantic ghost crab on a primary dune.

Saw palmetto block print I carved in 2013

Live oak (Quercus virginiana) a true stand-out species of the Maritime forest, with leaves that stay green all year.

Maritime forest seen along Jones Marsh. To the right, Sabal palmetto,( or cabbage palmetto) and to the left, Cedar.

Springer Mountain and Three Forks Creek on Appalachian Trail

These next few blog posts will be dedicated to a class I am currently taking at Georgia State University concerning the natural environments of Georgia.

We hiked the start of the Appalachian trail up to Springer Mountain and then down to Three Forks trail on September 30,2016. From the top of Springer Mountain one can see an example of an Montane Oak forest community and then make their way down the mountain and continue along as the Appalachian Trail changes into an Acidic Cove community.

The AT stretches 2,189 miles from Springer Mountain in Georgia to Mount Katahdin in Main. The trail was proposed by regional planner Benton Mackaye in October of 1921,who originally envisioned the trail as an escape from urban-ism complete with recreational and farming camps that would create jobs as well as promote conservation. He rallied other city planners and officials in support of the trail until the first meeting of the Appalachian Trail Conference of 1925. The decisions of the Appalachian Trail Conference ultimately led for the volunteer based trail system to be protected from development. In 1937 the trail was completed, but World War as well as natural disasters took a toll and and would be hikers and volunteers were sent to war. The first thru-hike was completed in 1948 by Earl Shaffer who aimed to walk the "Army out of is system". Emma Gatewood, a mother of 11 and grandmother to 23, became the first woman to complete a thru-hike in 1955 at the age of 67. The Today, an estimated 2 to 3 million people hike the AT every year, with a few hundred of those completing a "thru-hike". Today the trail is almost entirely protected and managed by the Appalachian Trail Land trust, who continue to monitor the trail from development to keep it a natural and serene refuge, free of commercial developments.

The highlight of this hike was seeing a mighty Eastern Hemlock about half a mile off the Appalachian trail that has still survived in spite of logging in the past and the invasive Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HWA) of the present. HWA has devastated millions of hemlock trees since it was first discovered in the USA in the 1950's and continues to spread. Once infected, a tree can die within 2-4 years. Currently, strategies to control the parasitic incest include both insecticides and introduction of the Sasajiscynus tsugae beetle which eats HWA.

We hiked the start of the Appalachian trail up to Springer Mountain and then down to Three Forks trail on September 30,2016. From the top of Springer Mountain one can see an example of an Montane Oak forest community and then make their way down the mountain and continue along as the Appalachian Trail changes into an Acidic Cove community.

The AT stretches 2,189 miles from Springer Mountain in Georgia to Mount Katahdin in Main. The trail was proposed by regional planner Benton Mackaye in October of 1921,who originally envisioned the trail as an escape from urban-ism complete with recreational and farming camps that would create jobs as well as promote conservation. He rallied other city planners and officials in support of the trail until the first meeting of the Appalachian Trail Conference of 1925. The decisions of the Appalachian Trail Conference ultimately led for the volunteer based trail system to be protected from development. In 1937 the trail was completed, but World War as well as natural disasters took a toll and and would be hikers and volunteers were sent to war. The first thru-hike was completed in 1948 by Earl Shaffer who aimed to walk the "Army out of is system". Emma Gatewood, a mother of 11 and grandmother to 23, became the first woman to complete a thru-hike in 1955 at the age of 67. The Today, an estimated 2 to 3 million people hike the AT every year, with a few hundred of those completing a "thru-hike". Today the trail is almost entirely protected and managed by the Appalachian Trail Land trust, who continue to monitor the trail from development to keep it a natural and serene refuge, free of commercial developments.

The highlight of this hike was seeing a mighty Eastern Hemlock about half a mile off the Appalachian trail that has still survived in spite of logging in the past and the invasive Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HWA) of the present. HWA has devastated millions of hemlock trees since it was first discovered in the USA in the 1950's and continues to spread. Once infected, a tree can die within 2-4 years. Currently, strategies to control the parasitic incest include both insecticides and introduction of the Sasajiscynus tsugae beetle which eats HWA.

Appalachian Trail Marker at the summit of Springer Mountain.

views from trail marker at summit of Springer Mountain

(Quercus alba) This old growth gnarly white oak at the top of Springer Mountain has been shaped by many years of facing harsh winds and freezing temps which as one can see have snapped off several branches in the past. Many of the old growth oaks at this elevation share these same features which is also why it is thought that they were over looked by loggers in the early century and left to survive.

The same white oak as pictured above, with an "arborglyph"

hiking up the Springer Mountain trail

moss and lichen

red maple leaf (Acer pensylvanicum) is a common tree found in the Montane oak forest community. ferns and goldenrod wildflowers scatter on the forest floor.

an endemic Georgia Aster ( Symphyotrichum georgianum) which was nominated by the Georgia Native Plant Society as the 2015 plant of the year,

classmates passing thru a canopy of rhododendron in the lower elevation Acidic cove forest near Three Forks Creek

Acidic cove forest on Appalachian Trail

The ground is damp and the trees and forest floor are covered with moss and lichen.

Hair cap moss (Polytrichum commune)

moss and lichens on tree bark

the base of this hemlock tree

this Galax urceolata covering the ground along a stand of hemlocks is now a protected plant in many places due to illegal harvesting because the evergreen leaves are popular in the floral industry.

A group of mighty hemlocks (Tsuga canadensis) which have died from being infested with Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HWA)

dead hemlock bark

living hemlock bark. this is just a close up of a tree we measured that may classify as a new state champion. the bark is home to a healthy community of moss and lichen and the holes are evidence of woodpecker foraging

Battus philenor

we spotted a Pipe vine swallowtail, on the trail (although I am using an image instead of one that I took from my neighbor's garden) It is a poisonous species whose pattern and colors are mimicked by many, including the black variation of the female Eastern swallowtail butterfly.

Cloudland Canyon

These next few blog posts will be dedicated to a class I am currently taking at Georgia State University concerning the natural environments of Georgia.

600 million years ago the area of Coudland Canyon was once covered by a shallow sea full of tiny marine organisms, some of whose remains would be pressed into the limestone bedrock and are still visible today within the exposed rock at sites like Ruby Falls within the Mountain. Cloudland Canyon lies on the Southern end of Lookout Mountain, which was formed over 250 million years ago during the collision of North American and Africa along with the formation of the Appalachian Mountain range. This collision bent and folded the existing layers of rock, creating cracks that allowed water through to begin the process or erosion that would eventually create the surrounding lower elevation areas such as Cloudland Canyon. So essentially, Cloudland Canyon was formed from erosion, and long ago the surrounding elevation was all much higher. The Appalachian Mountains used to be a mighty tall range that is still slowing eroding into the sea. What we see at Cloudland Canyon is the product of that erosion and a forest that was once under the sea, and if current trends of sea level rise continue, it may once again be.

Several ecological communities can be found here, such as Oak-Pine-Hickory forest and pine-oak woodlands.

The Acidic Oak-Pine-Hickory forest community seen here includes tree species such as Southern red oak (Quercus falcata), White oak (Quercus alba), Rock Chestnut oak (Quercus montana), Post oak (Quercus stellata), Scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea), Shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana), sourwood (Oxydenfrum arboreum), and flowering dogwood (Cornus florida).

The sandy, acidic soils created by sandstone and shale bedrock support acid loving ericaceous shrubs such as mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia), hillside blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), sparkle berry (Vaccinium arboreum), fringe-tree (Chionanthus virginicus), and witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) .

The park is also home to Acidic Cliff and Rock Outcrop communities, which support mountain spleenwort (Asplenium montanum), partridge-berry (Mitchella repens), and hairy-southern bush-honeysuckle, which makes me laugh and just to name a few.

"Located on the western edge of Lookout Mountain, Cloudland Canyon is one of the largest and most scenic parks in the state. Home to thousand-foot deep canyons, sandstone cliffs, wild caves, waterfalls, cascading creeks, dense woodland and abundant wildlife, the park offers ample outdoor recreation opportunities. Hiking and mountain biking trails abound. The most popular hiking paths include the short Overlook Trail, strenuous Waterfalls Trail and moderate West Rim Loop Trail. Mountain biking is available at the newly developed Five Points Recreation Area and along the Cloudland Connector Trail. The park also includes an 18-hole disc golf course, wild caves available for touring during select months of the year, a fishing pond, trails for horseback riding, picnicking grounds and numerous interpretive programs, especially on weekends. Guests seeking an overnight experience can choose from fully-equipped and comfortable cottages, quirky yurts or several different types of camping and backpacking options. Come enjoy the great outdoors at Cloudland Canyon State Park."

http://www.gastateparks.org/CloudlandCanyon

On this day of early Fall October 15, 2016, North Georgia has been experiencing a severe drought and none of the waterfalls or spray cliffs in the park had water flow. Signs of drought could also be seen in many of the wilting ericaceous plants.

Several ecological communities can be found here, such as Oak-Pine-Hickory forest and pine-oak woodlands.

The Acidic Oak-Pine-Hickory forest community seen here includes tree species such as Southern red oak (Quercus falcata), White oak (Quercus alba), Rock Chestnut oak (Quercus montana), Post oak (Quercus stellata), Scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea), Shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana), sourwood (Oxydenfrum arboreum), and flowering dogwood (Cornus florida).

The sandy, acidic soils created by sandstone and shale bedrock support acid loving ericaceous shrubs such as mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia), hillside blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), sparkle berry (Vaccinium arboreum), fringe-tree (Chionanthus virginicus), and witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) .

The park is also home to Acidic Cliff and Rock Outcrop communities, which support mountain spleenwort (Asplenium montanum), partridge-berry (Mitchella repens), and hairy-southern bush-honeysuckle, which makes me laugh and just to name a few.

"Located on the western edge of Lookout Mountain, Cloudland Canyon is one of the largest and most scenic parks in the state. Home to thousand-foot deep canyons, sandstone cliffs, wild caves, waterfalls, cascading creeks, dense woodland and abundant wildlife, the park offers ample outdoor recreation opportunities. Hiking and mountain biking trails abound. The most popular hiking paths include the short Overlook Trail, strenuous Waterfalls Trail and moderate West Rim Loop Trail. Mountain biking is available at the newly developed Five Points Recreation Area and along the Cloudland Connector Trail. The park also includes an 18-hole disc golf course, wild caves available for touring during select months of the year, a fishing pond, trails for horseback riding, picnicking grounds and numerous interpretive programs, especially on weekends. Guests seeking an overnight experience can choose from fully-equipped and comfortable cottages, quirky yurts or several different types of camping and backpacking options. Come enjoy the great outdoors at Cloudland Canyon State Park."

http://www.gastateparks.org/CloudlandCanyon

On this day of early Fall October 15, 2016, North Georgia has been experiencing a severe drought and none of the waterfalls or spray cliffs in the park had water flow. Signs of drought could also be seen in many of the wilting ericaceous plants.

Virginia pine (Pinus virginia)

wild blueberries (Vaccinium arboreum)

dry shrubs and rock outcroppings

Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides)

Drought conditions have severely wilted this rhododendron, which likes a moist and acidic environment.

Calcareous cliff rocks in Cloudland Canyon are high in Calcium and limestone and are easily eroded.

Rhododendron maximum

( this is a photo of Rosebay rhododendron seen in bloom on an earlier trip to the canyon in mid-summer)

Kalmia latifolia

(Mountain laurel, also seen earlier in the year when it was in bloom early summer)

turkey tails (Trametes versicolor) are a common polypore mushroom found in many parts of the world and has been used medicinally in many cultures as well.

Sassafras sapling (Sassafras albidum), a fragrant tree made locally famous for it's use in brewing root beer

Wild Hydrangea (Hydrangea arborescens)

Autumn leaf butterfly competing with paper wasps for the sap of this tree.

the bright beginnings of the unmistakable and edible Chicken of the Woods fungus, also known as sulphur shelf , (Laetiporous sulphureus)

The white spots seen on this young Hemlock tree are a colony of the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HMA), which is an invasive insect imported from Asia that has decimated Georgia's Hemlock populations and continues to spread quickly across the state.

scenic views from the rim trail show the exposed bedrock cliffs

Davidson-Arabia Mountain Nature Preserve

These next few blog posts will be dedicated to a class I am currently taking at Georgia State University concerning the natural environments of Georgia.

Granite outcrop communities have been said to be the crown-jewel of Georgia natural communities because they feature a rare suite of endemic or nearly endemic species, and Georgia has more of these outcrops than any other state. (L.Edwards,The Natural Communities of Gerogia p.303) Mount Arabia is a perfect example of one of these communities, consisting of granitoid rocks known as Lithonia gneiss which is a nomenclature distinct to Mount Arabia. It is with much awe that I also mention that although Arabia Mountain, Panola Mountain, and Stone Mountain are all granite outcroppings within 20 miles of one another they each are composed of a distinctly different composition of granitoid rock. Mount Arabia is a perfect example of the healthy successional plant community that is adapted to all three of these just mentioned. The many stages of succession can be observed here, starting from Xanthos and Endolithic lichens and Elf Orpine, and moving all the way up to Virginia Pine trees and Muscadine Vines. Many of these plants are endemic and/or federally endangered, so be careful where you step! If you plan on exploring the mountain in the summer please be aware of ticks, which are abundant here! This is a truly special place that we are lucky to have so close to the city and still largely intact.

Find out more about the trails and history here: arabiaalliance.org

Here are some of our field findings from Mount Arabia on September 16th, 2016:

(Photos taken from trails located in Davidson-Arabia Mountain Nature Preserve)

rock moss, (Grimmia laevigata)

The top of the mountain was dry and sunny, as Georgia had been experiencing drought conditions. Pictured here is rock moss, which can appear dark grey or even black when dry but puffs up and turns green when wet. Here the green colored rock moss has been watered by our teacher with a water bottle.

Ornate Chorus Frog (Pseudacris ornata) found camouflaged in one of the water filled seepage pools on the mountain top.

water-filled seepage pools on the rock outcropping create a temporary wetland habitat of standing water and mineral breakdown

Haircap moss (Polytrichum commune) and Reindeer lichens (Cladonia spp. and Cladina spp.) growing on rock outcrop

After flipping through field guides and looking through several online data-bases, this appears to be

Puck's orpine (Sedum pusillum),

a federally endangered species that is very similar to the famous Elf orpine, but prefers to grow in the shadier borders of the granite outcrop and not in the vernal pools. It tends to be found under the shade of the Juniper tree or in cracks in the granite, such as pictured here. If can also be green when found in the shade but develops a more reddish color when exposed to full sun.

Pine weed (Hypericum gentianoides) is well adapted for the harsh environment and full sun of the granite outcrop with it's modified photosynthetic stems.

The rare and endemic Confederate daisy (Helianthus porteri)

exposed rock that has been cut in early quarry operations

with only 11 known sites of this species left, federally endangered Elf-orpine (Diamorpha cymosa or Diamorpha smallii)

seed pod awaits the harsh summer sun before germinating in the Fall

Xanthoparmelia conspersa,

a slow growing lichen seen of a quarried granite slab just off the walking trail. I never tire of getting lost in the patterns of lichens.

Glen Lake Nature Preserve

(update, March, 2022)

[I wrote this blog post before the local mushroom and foraging groups of social media had amassed numbers of fungi thirsty forest tramplers. I never harvested mushrooms here because I believe that a "preserve" should be just that. A place to "preserve", and not to take. Nevertheless, it has been years (possible since this original blog post) since I have seen any edible or medicinal mushrooms here. ]

dog-day cicada exoskeleton, Tibicen canicularis

Eastern Swallowtail butterfly, Papilio glaucus

Daddy long legs spider on Beech tree leaves, Fagus Grandifolia

pleated ink cap mushroom, Coprinus plicatillis

unidentified fungus

swallowtail wings discarded and found in piles

trail view

tulip poplar beauty moth, Epimecis hortaria

umbrella magnolia, Magnolia tripetala

tulip poplar bloom

garden snail party

puff ball mushrooms

Magnolia grandiflora

Angel Oak

A visit to Angel Oak Tree and marshes near Charleston, South Carolina.

Lives are lived

and rivers flow.

Our thoughts

and feelings,

layers of current

stirring silt

and carving rock.

Eventually,

carrying us out to sea.

The creeks and streams

like capillaries,

fortifying the spaces

inbetween.

Connecting air to flesh

to earth

like the roots

and leaves of a tree.-Rebecca Cristante

creek poetry

We spent the afternoon sifting through our backyard creek.

Collection as follows: eastern swallowtail butterfly, tulip poplar leaves, shoe sole, bic lighter, quartz crystal, and various unidentified clay rocks

Swallow tail wings were piled in great numbers, eaten by some creature who seems to collect them all in one spot to feast before discarding the leftovers.

Lake Seminole

Pictured here is my Great-Grandfather, Fred Faircloth. circa 1918.

My Grandfather was a field laborer, and homesteader, like many were in Southwest Georgia in those days. He worked his body to the bone to afford a small plot of land in Seminole County, Georgia, close to the site of Lake Seminole before it was flooded and damned into one of the biggest lakes in Georgia

as it is today. He grew vegetables for the family, and raised turkeys and chickens for the meat and eggs. Deer were hunted and eaten as well. Some days he worked as a laborer and some days he went out with a group of men, mostly poor and black, to collect turpentine from the long leaf pines. They would carry huge metal buckets strapped to their backs for collecting the sap. This, of course, was before all the Long Leaf Pines were cut down. I grew up playing on his swamp land in the house that he built by hand. It was here that I was motivated to identify species of snake, mostly in attempt to convince my grandmother to stop killing the non-venomous ones.

When I think of the word "farmer", my great-grandfather is who I think of, even though he might not have called himself one at the time. His old house has since been sold and the first thing the new owners did was cut down the massive old oaks on the property to sell them for timber.

As they say, there is a "special place in hell".

Kolomoki Mounds, Blakely, Georgia

Kolomoki Mounds is the largest and oldest protected Woodland Indian site in the southeastern United States.

Native plant, (yucca filamentosa)

(gopherus polyphemus)

The sandy soils here in the Southwest Georgia coastal plain are home to the endangered gopher tortoise. Several burrows, including this one, can be found within walking distance of the visitor's center.

When I was a little girl I remember going on a field trip to visit Kolomoki mounds. Looking back, I am so glad our teachers found this place important enough to visit, even though at the time the very disturbing theatrics performed scared the bejesus out of all of us. Inside the museum and visitors center one can see the actual remains of an excavated mound, and at that time actors performed some kind of bad rendition of a ritual dance full with feathers and stereotypical pow wow chants as if they got the entire skit from a black and white country western movie. I just remember having this utterly horrible feeling that THIS IS SO WRONG. It was a desecration of a sacred space that was being turned into a tourist attraction. I honestly don't know if they do this anymore, but if they do I just hope that someone with actual native blood is being paid for the performance.

(Solenopsis invicta)

also known as the Red Imported Fire Ant, making one of their colonies on this young Long Leaf Pine tree. Be careful of these ants if you hike here, because they attack quickly when disturbed and inflict a painful sting that will burn and itch for days.

Providence Canyon

Providence Canyon is a little off the beaten path and a short drive away from both Kolomoki Mounds historical site and White Oak Pastures,( you could actually visit all three of these places in one day). White Oak Pastures provides excellent meals and lodging if you decide to lengthen your explorations.

http://gastateparks.org/ProvidenceCanyon

Located about 150 miles southwest of Atlanta in the Coastal Plain eco-region of Gerogia, Providence Canyon was formed over 150 years ago from agricultural erosion. Forests were cleared on a massive scale for cotton fields and timber, and with no vegetation to protect it the remaining topsoil was washed away by rains, creating the deeply eroded gullies and canyons that are still slowly eroding today. I found a geologic guide by Lisa Joyce, which noted to a story that the canyon was started by water leaking from the roof of a barn that used to sit on top of it. While this may not be true, you gotta love a southern folk tale. We are full of them.

Because the canyon is created by loose sediments, rapid changes can occur suddenly and visitors are warned to be extra careful in wet or rainy conditions.

The exposed clay formations of the canyon gives us a look back in time, and through geological analysis one can even see where the ocean once flowed over the area, lowered, and flowed again. Some of the major sediments present are iron-ore, mica, and kaolin clay.

We visited Providence Canyon on a sunny Thanksgiving Day, 2015. It was a typical South Georgia day in November, just chilly enough for a light jacket and hardly no wind at all.

The slightly running stream of water and minerals at the bottom of the canyon is full of iridescent particles that are hard to see from the photographs alone.

Kaolin clay mining production near Providence Canyon in Bluffton, Georgia. Photo take 11/24/2016

http://gastateparks.org/ProvidenceCanyon

Located about 150 miles southwest of Atlanta in the Coastal Plain eco-region of Gerogia, Providence Canyon was formed over 150 years ago from agricultural erosion. Forests were cleared on a massive scale for cotton fields and timber, and with no vegetation to protect it the remaining topsoil was washed away by rains, creating the deeply eroded gullies and canyons that are still slowly eroding today. I found a geologic guide by Lisa Joyce, which noted to a story that the canyon was started by water leaking from the roof of a barn that used to sit on top of it. While this may not be true, you gotta love a southern folk tale. We are full of them.

Because the canyon is created by loose sediments, rapid changes can occur suddenly and visitors are warned to be extra careful in wet or rainy conditions.

The exposed clay formations of the canyon gives us a look back in time, and through geological analysis one can even see where the ocean once flowed over the area, lowered, and flowed again. Some of the major sediments present are iron-ore, mica, and kaolin clay.

We visited Providence Canyon on a sunny Thanksgiving Day, 2015. It was a typical South Georgia day in November, just chilly enough for a light jacket and hardly no wind at all.

The slightly running stream of water and minerals at the bottom of the canyon is full of iridescent particles that are hard to see from the photographs alone.

Kaolin clay mining production near Providence Canyon in Bluffton, Georgia. Photo take 11/24/2016